Cathinone (2-amino-1-phenyl propanone) is the naturally occurring psychostimulant and the major active constituent of khat, the leaf of the Catha edulis bush that has been chewed recreationally in East Africa and Middle East for centuries. Cathinone is the b-keto analog of amphetamine (1-phenylpropan-2-amine) and modifications to the basic structure of the cathinone result in cathinone derivatives, such as 4-methylmethcathinone or mephedrone. This publication will review one important scientific study of mephedrone that will open up your understanding in its effects and features.

Mephedrone (4-MMC; 1-(4-methylphenyl)-2-methylaminopropane-1-one) was first synthesized in 1929 and is one of the most potent derivatives of the cathinone. Mephedrone abuse became an emerging public health problem in late 2000s, affecting adolescent and young adult users worldwide. Growing number of reports on the synthetic cathinone abuse highlights the serious physical and psychological risks.

Similar to other phenylethylamines, mephedrone acts as a dopamine and serotonin transporter substrate, disrupting vesicular storage and dramatically increasing dopamine and serotonin levels, thus eliciting powerful psychostimulant, enactogenic, and hallucinogenic effects.

Potency, low cost, and wide availability of mephedrone made it desirable substitute to more expensive illegal drugs that share similar mechanism of action, such as amphetamine, ecstasy (MDMA), and methamphetamine. Numerous reports state that mephedrone is also used as a partial filler of ecstasy preparations, thus drastically increasing risk of over-dose and adverse side effects.

Study of Mephedrone

We included many questions on mephedrone in our yearly online sentinel drug user survey among a group of seasoned polydrug users who are participants in the UK dance music scene in order to get preliminary data on the health dangers of this substance.

Despite its prior obscurity, our data revealed that in 2009, 43% of the 2220 respondents had used mephedrone; it rated as the sixth most popular drug that year (after alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, cocaine, and MDMA) and was thought to create a “greater high” than cocaine. Users of novel or emerging pharmaceuticals are a mostly untapped market that might be challenging to reach using conventional methods.

Online polls are useful for quickly illuminating a new substance on the drug scene, but they have certain drawbacks, such as the inability to ask in-depth questions. Moreover, for new or emergent substances, it is difficult to assess the validity of reports because the substance may acquire several colloquial names with no assurance for the user of the precise nature of the substance’s contents.

In order to obtain comprehensive information about the health risks of mephedrone use, we invited participants in our online survey to participate in a face-to-face, anonymous telephone interview. The primary goals of this online survey were:

- Describe in words the circumstances under which participants began using mephedrone and the nature of their mephedrone use.

- Evaluate the full range of mephedrone’s acute effects and withdrawal effects.

- Assessment of the prevalence of addiction symptoms.

- In addition, we conducted a toxicological analysis of the bodily fluid (urine) samples we took from the participants in our online survey.

Research method

This telephone study was cross-sectional, organized, and included a toxicological evaluation of cathinone chemicals in urine. 218 users of mephedrone out of the 947 who completed our online survey and supplied contact information had shown an interest in speaking with us about more study.

We continued to contact and secure personal telephone interviews with this group until our target of 100 users was reached. The average interview took 25 minutes to complete; the standard deviation (SD) was 6.3. All participants reported using mephedrone at least once in the preceding 12 months and were all 18 years of age or older (mean age, 25 years, 23 female, and 86% in job or education).

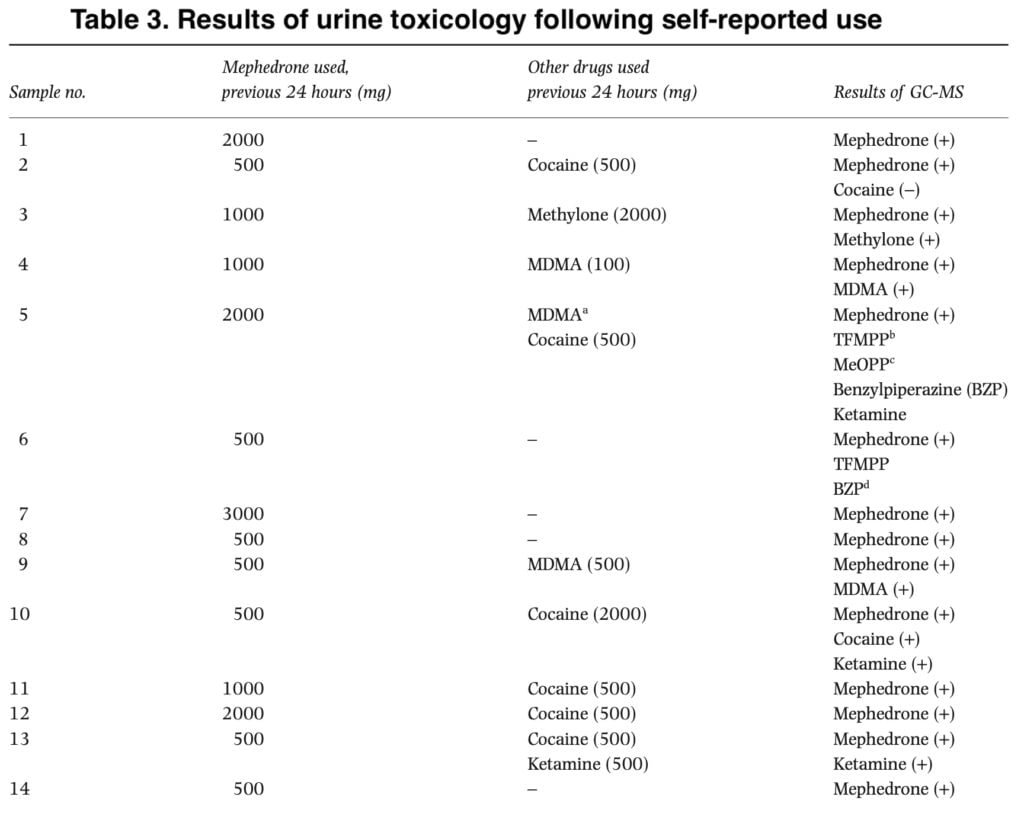

In line with the sample they had been taken from, there was a high lifetime prevalence of MDMA and cocaine usage (96% and 92%, respectively). We questioned the subject if they planned to use mephedrone again during the next month after the interview. A day after using mephedrone, participants were asked if they would be willing to provide a urine sample to the research lab for investigation of cathinones and other substances. Among the 47 participants who intended to use mephedrone again in the next month, 26 (55%) consented to provide a urine sample.

We received a total of 14 samples (54%) for analysis. We analyzed the obtained biological liquid by gas chromatography mass spectrometry in order to identify the following compounds: Cath, MC, EC, 4-MMC, 2-FMC, 3-FMC, 4-FMC, DMC (dimethylcathi- none), 4-MAB (4-methoxymethylaminobutyrone) and 4-MoxyMC (4-methoxymethcathinone).

We extended the questions from our prior online poll and used them to build a short, organized telephone interview schedule. We created a 20-minute interview with 61 items after doing cognitive and pilot testing. We created a list of 12 withdrawal symptoms and 28 typical stimulant or empathogenic medication effects (both good and negative, physical and psychological).

On a Likert-type rating scale, participants were asked to indicate how frequently they had experienced each effect while using mephedrone (‘never, once, occasionally, or most of the time’; scored 0-3) as well as the average degree of each effect (‘light, moderate, or powerful’; scored 1-3).

We calculated the product of the frequency and intensity of effect ratings to create a variable with a score range from 0-9, with three equivalent scores: once moderate and sometimes mild; once intense and most of the time mild; and sometimes intense and most of the time moderate. For the risk profile in this report, we present the basic prevalence of each effect (experienced “once” or more frequently) and we computed the product of the frequency and intensity of effect ratings.

The participant was questioned about whether they had ever had a persistent desire or strong urge to use the drug, had ever been concerned about doing so, or had ever had friends or family express concern about their use of mephedrone.

We included seven dependence items adapted from DSM-IV-TR for use in the study. For brevity, we recognized that we would not be able to include a formal clinical diagnosis of dependence in the interview. For brevity’s sake and because mephedrone was a legal substance at the time of the survey and the item about repeated substance-related legal difficulties would not clearly apply, we also removed the four DSM drug addiction items.

Discussion and interpretation of the results

The first mephedrone session for participants lasted a median of 6 hours, during which a median of four doses—each averaging 97 mg—were administered. Overall, a total of 500 mg of mephedrone was ingested throughout the session. 89 individuals reported using alcohol, 17 reported using cocaine, 23 reported using MDMA, 34 reported using cannabis, and 24 reported using ketamine for the first time.

Participants said they had used mephedrone for an average of 6 months at the time of the interview. The participants were then asked to reflect on how their usage had evolved since they first used mephedrone, and we noted the usual first dose amount they had taken in a recent session. During a typical session, the majority (83 of 100) administered their first dose (average first dose 125 mg) as a ‘line’ (79% intranasally, 9.9% by wrapping in a cigarette paper and swallowing, and the remainder by tipping some mephedrone powder into a drink).

The normal session lasted for an average of 10 hours, during which an average of 5.5 doses were taken, with an average gap of 60 minutes between doses, and an average dosage of 1000 mg. In this average session, 82 people reported using alcohol, 36 reported using marijuana, 35 reported using ketamine, 26 reported using cocaine, and 23 reported using ecstasy.

None reported using mephedrone alone and the average group size of co-users was 10. Forty-seven participants reporting using mephedrone continuously for 48 hours or more; and among these participants the median number of continuous using days was 3.

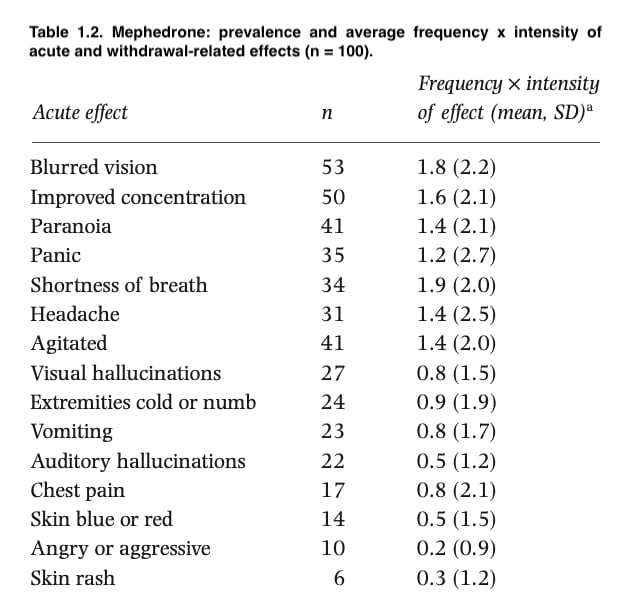

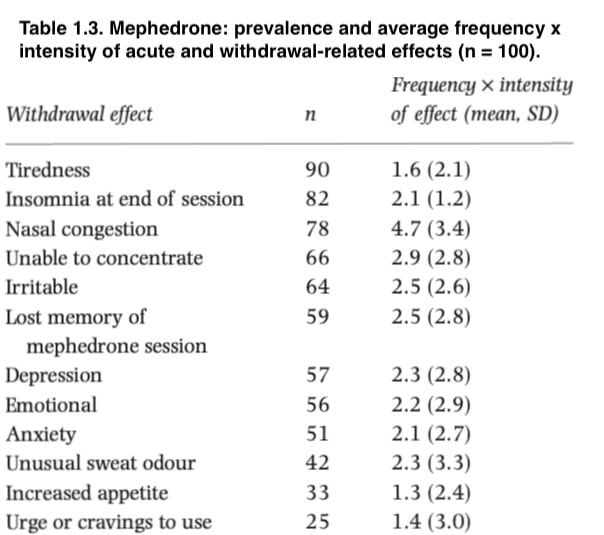

We converted the frequency of each symptom’s occurrence into a binary variable, either a symptom was ever experienced or not (the prevalence). The strength of each symptom was then determined by multiplying its actual frequency by its intensity, and the mean for each item was reported on this composite score.

Table 1 lists the frequency (ordered) and typical potency of mephedrone’s acute effects as well as associated withdrawal symptoms. The most common and severe acute effects were increased energy, euphoria, and talkativeness, whereas the most common withdrawal-related symptoms were fatigue, sleeplessness, nasal congestion, and attention deficit disorder (with nasal congestion the most intense effect).

An important difference between this study and others is the presence of toxicological analysis of urine. The subjective reports from our participants suggest that the stimulant class has a similar health risk profile, with a postulated mechanism of action that includes the release and inhibition of re-uptake of monoamine neurotransmitters.

The stated risk profile indicates that at the levels normally eaten by the study individuals, there is a relatively low occurrence of aggressive behaviors. The low potency and brief duration of action of mephedrone, which allow for titration of dosage and effect, may be to blame for the comparatively low prevalence of negative effects (compared to desired results).

This does not imply that using mephedrone is risk-free. It has been reported that consuming this chemical might cause certain severe and excessive sympathomimetic effects, such as intense agitation, aggressiveness, panic, thirst, disorientation, hyperthermia, seizures, cardiovascular dysregulation, and delusional episodes.

Concerning is the suggestion that mephedrone may have a dependency risk. About 30% of the patients in our study met three or more DSM-IV criteria for dependency. Increased tolerance, poor control, continuing to use mephedrone despite physical and psychological issues, and a strong need to use the drug were the main symptoms (the study did not inquire about within session development of tolerance).

The incidence of taking mephedrone for two or more consecutive days (47% of our sample) was similarly reflected in these symptoms. The authors acknowledge that the method employed to measure dependency does not result in a diagnosis of dependence; rather, we contend that the results are highly suggestive of mephedrone’s dependence potential.

Conclusion

We are aware of a number of research limitations. This is a fairly small sample of self-identified drug users, and it is unclear if the results can be generalized to the larger user community. We also note the potential for recollection bias when considering variations in dosages taken over time, the shaky accuracy of predicting average doses, and the potential for polysubstance usage to taint reported effect profiles.

The study’s advantages stem from the importance of quickly evaluating novel and developing medication trends. Sentinel samples from target populations are sometimes the only realistic way to get an initial assessment of a substance’s risk profile and can offer insightful information about emerging drug usage patterns. It is beneficial to provide fundamental information as soon as possible to users, decision-makers, and research audiences. Our use of a toxicological analysis also indicated perfect agreement between self-report and mephedrone in urine detection.

The discordant results for the presence of cocaine in samples 2, 5 and 11–13, where there was reported use, may reflect the low purity of cocaine currently variable in the United Kingdom. We also think it’s plausible that in a social context, participants who may have used other drugs would not be able to tell cocaine apart from other stimulants like ephedrine and mephedrone.